I'm sure you are familliar with Crayford's Triarchy. Their "Save the Khan" and "Metal Messiah" singles definitevely were more new wave than heavy metal, but anyway they gained attention of those fans who love rock music without boundaries and have an eclectic collection of records – from Rush to Iron Maiden to The Strangelers to whatever they like. The legacy of Triarchy is well documented by High Roller Records who released three compilations of the band. Last year Mike Wheeler, Triarchy's singer/bass player, put out another retrospective release, "The High Roller Tapes", via Bandcamp. Could I miss an opportunity to blow the dust off the Triarchy's history book? No way!

In 2022 Triarchy released “The High Roller Tapes” compilation via bandcamp. What was the purpose for this release?

Triarchy split up in 1982 (or thereabouts) and since then we’ve had album-length material released or re-released on 3 previous occasions in CD or vinyl form. During this time, our stuff has also been ‘unofficially’ uploaded in digital form to platforms such as YouTube many many times, but there had been no official digital release. Given that that’s increasingly the way people listen to music these days, I thought it was definitely time to put some of our music out there in that form, on Bandcamp, Spotify, iTunes etc., with proper remastering suitable for such platforms.

Fans of NWOBHM usually prefer vinyls and CDs, so how are things going with the digital release?

Despite the fact that we did virtually zero promotion for the digital release (I’ve been too busy with my new solo stuff), there’s been a steady and increasing stream of listeners, especially on Spotify. I guess that people are finding the release via searches and playlists. So, under the circumstances, I’m very happy with how things have gone.

What do you think about the reissues which came out on High Roller? Why was it mostly Mark Newbold who did interviews in support of the reissues? Weren’t you interested in that at the time?

I think the re-mastering, artwork, and packaging for both the High Roller reissues were really excellent, and in both cases it gave us the opportunity to release material that hadn’t been available previously, including tracks like "Rockchild", "Wheel of Samsara", and a live version of "Suicide City". We are really grateful to High Roller for supporting us in the way that they did, and for letting us use the masters from the "Save the Khan" album as the basis for the recent digital reissues (hence the title "The High Roller Tapes").

Although I still play music, my livelihood turned out be as an academic (I’m now Professor of Philosophy at the University of Stirling), and during the period of the High Roller reissues I was very busy building and consolidating that career. Mark had more time to support the releases with interviews and he did a great job.

|

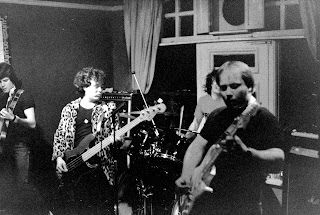

| Mike Wheeler at The Red Lion. Picture by Rob Grain |

In my teens, I was a perfectly competent electric rhythm guitarist, but solos were never my thing. I just didn’t have the motivation to learn to play rock lead. As the band developed through our mid-teens, I increasingly enjoyed bass playing and that was where I settled at the time. I was a big fan of bass players who made that often in-the-background instrument a focus of the listener’s attention, without simply playing bass solos – bassists such as Jack Bruce and Geddy Lee – and I hope that that comes through on Triarchy’s recorded output. It was definitely a feature of our live shows.

I was never a keyboard player in the tradition of those prog rock or heavy rock keyboardists who were often classically trained and technically gifted pianists. For me it was mostly about adding simple melody lines and occasional chord effects – more Depeche Mode than Deep Purple. We wanted to use synthesizers and I learnt to play keyboards well enough to achieve what we wanted. I remember once being in a house in LA where there was a Steinway piano and the owner, having heard that I could tinkle the ivories a bit, asked me to play something. I think she was pretty disappointed by the standard of what I produced!

Did you like the way the music developed from the early 70’s to the 80’s? What era was/is your favourite?

All the different periods of Triarchy had their pluses – from the mad invention and frequent direction changes of the earlier days, to the mix of new wave and heavy rock influences that characterised the period with Graham Legg on guitar, to the introduction of more blues-y elements with Brian Galibardy on guitar, to the more out-and-out heavy rock of the final period with Eddie Webb (guitar), Pete More (guitar) and Mark Annal (drums). Speaking purely personally, my favourite period of Triarchy was probably the line-up with Mark Newbold and Brian, because that’s when we did most of live work in direct support of the "Save the Khan" and "Metal Messiah" singles (we only ever did 1 gig with Graham), and I think the live sound we developed with Brian, which revolved around a close musical understanding between the three of us – a bit like a sort of NWOBHM Cream – was really distinctive within the NWOBHM movement.

Mark Newbold mentioned that you both were equally influenced by bands like Rush. ELP on one hand and Blondie, The Stranglers on the other. Would you agree with Mark?

Yes, absolutely. The fact that, from 1976 onwards, Mark and I we were listening to punk and new wave bands as much as, if not more than, prog and heavy rock was a massive influence on how Triarchy developed.

Triarchy was a pretty natural name for a three-piece band that you were, but who came up with that? My guess it was Mark Newbold as he was into history. Did you consider other names by the way?

I’m afraid I have no memory of who came up with the name, but what is true is that we called ourselves Triarchy from the very early days. We did have a brief flirtation with punk when we called ourselves The Raiders for a few weeks, and for a short while we joined up with some other local musicians in a 4 or 5 piece band (I can’t remember now) called Raging Silence, but these were short-lived experiments that quickly fell apart. We always went back to Triarchy. The name became a bit of a problem when the band morphed into a 4 piece during its final incarnation, but by then we were known because of our records and so we just stuck with it, ignoring the numerical clash!

It was just a garage (or, more accurately, a front room) band, because the line-up never performed live. However, there was a lot of musical experimentation (we often changed instruments) and we didn’t start out by playing covers. From day one, we were writing our own music. The attitude of that band really set the foundations for the later line-ups. Martyn just lost interest in playing music, but he became a key supporter of the band who came to gig after gig after gig.

When and how did you find Derek Lomas, the guitarist? How long did he stay with the band and did he bring any riffs or complete ideas which you later used in your songs? Why did you replace him with Graham Legg?

I can’t remember for sure how we found Derek – it may well have been an advert in a local shop window! – but he certainly brought his own ideas into the band. Indeed there were a couple of Lomas-penned tunes on the very first Triarchy demo that we now call "The Balham Tapes", because of the location of the studio where they were recorded. The titles of some of Derek’s songs sounded embarrassingly like early 70s macho band tracks now (e.g. "Loose Livin’ Woman"), but in fact they were really interesting tracks with a very different style to my own writing – very R’n’B, a sort of heavy metal Dr Feelgood. Indeed, his playing style was a sort of mixture of heavy metal, Wilko Johnson and James Williamson (The Stooges). In the end, I think Mark and I had a commitment to the band going in certain musical and professional directions that Derek didn’t want to sign up for, so things sort of fell apart. I’m pretty sure Graham came along in response to an advert we placed in the music paper, Melody Maker.

How did you get gigs being an independent band? Do you remember your first gig outside Gravesend? Was it a win or was it more like a lesson to learn?

Although we ended up having a close relationship with Gravesend, because of our regular gigs at The Red Lion there, the band was actually based in Crayford, which is further in towards London, and our first gigs were in the local Crayford/Dartford area. Initially, we hired out halls and promoted our own gigs, at venues such as the Dartford YMCA, a place where we continued to play pretty much right through our time. We would put up posters around the local towns and put adverts in the music press gig listings. Once we’d recorded and released the "Save the Khan" single, we would simply send that off to established venues to see if they would book us. Because, luckily, the single immediately attracted music press interest and air play, we could send it over with a bunch of press cuttings, so that strategy was pretty successful. That’s when we started playing regularly at The Red Lion in Gravesend and at another great venue called The White Swan in Blackheath. Gigs at these venues were almost always a blast, with solid local crowds topped up by a travelling band of hardcore Triarchy followers – definite wins.

I guess it was Red Lion where all the mischief in Gravesend happened. What are your memories about the place and its owner Terry Lee?

The Red Lion was a decent sized (but certainly not huge) pub on the edge of an industrial estate. When Triarchy played there, the stage was in the bar, rather than in a separate hall as it was later, which gave the place a buzzing atmosphere. We played there a lot and got on well with Terry Lee. Terry was also the sound man (he was a really good sound engineer and used to bring his PA along and do the sound for us at other venues), a real character, and a massive enthusiast for live music. I believe that, in 2018, he celebrated 40 years of promoting live music at the venue. During the period we played there (1980-82), it championed the NWOBHM scene and built a strong home crowd. We owe Terry a debt and I’ll always have super-fond memories of the place.

What were your biggest shows/crowds and what were the most embarrassing moments during live shows?

I suspect that the largest crowds we ever played to were at a venue called The Horseshoe in Tottenham Court Road, London, next door to the Dominion Theatre. Last I heard, it had been turned into a Garfunkel’s Restaurant, but in the early 1980s it held heavy rock gigs on Sunday evenings and we played a series of very successful dates there with the Annal/More/Webb line-up of the band. I remember we played several double-headers with a really great band called Overkill who deserved a lot more success than they actually achieved.

You shared the stage with Vardis, EF Band and probably some others. How did their fans react on you as you were more proggy and less “metal” so to say?

I really don’t remember having any big problems with other bands’ fans. I mean I’m sure plenty of them didn’t like us, because we weren’t a "down the line" heavy metal band, but we seemed to go down well with a wide range of crowds – including when we played a Rock Against Racism gig with a magic reggae band called The Mighty Shades. I do remember the owner of The Starting Gate in Milton Keynes telling us that he would see the same people in the heavy rock crowd night after night, except for when we played there, when a different audience would show up. That’s maybe evidence that we had a different crowd, one that definitely intersected heavily with the usual NWOBHM followers, but which attracted other music fans too.

In 1978 the band recorded a 4-track demo. What songs beside “Hiroshima” were on it? Does this record still exist? If yes, don’t you want to release it?

Actually it’s a 6 track demo that, as I mentioned earlier, we refer to as "The Balham Tapes". It’s the Lomas/Newbold/Wheeler line-up. The track listing is: "Plastic People"; "Suicide City"; "Loose Livin’ Woman"; "She Don’t Care"; "Victims"; and "Hiroshima". "Plastic People" and "Victims" are much punkier than the material for which we became known. "Loose Livin’ Woman" and "She Don’t Care" are two of the songs mentioned earlier that were penned by Derek Lomas. "Hiroshima" and "Suicide City" became lynchpins of the NWOBHM Triarchy set. It’s a pretty rough and ready bunch of recordings (all recorded in one day, mostly live, on a 4-track machine) and although it has its charms (Victims is a real personal favourite of mine), I have been thinking of it more as a historical document than something I would want the world to hear! Still, now that you’ve mentioned it, I might take another listen. These days, when it’s so easy to release material digitally, it’s more common for bands to make this sort of historically interesting stuff available to listeners, so it’s definitely an option.

In one interview Mark mentioned such songs as “Suicide City”, “Hey Mister Death”, “Lies”, “Plastic People”, “Sex Electric” and “All you Despise”. Did you record or rework any of them?

All these songs were part of the Triarchy repertoire when Graham Legg was the guitarist, but most dropped out of favour as we produced new songs. "Suicide City", however, remained in the live set right through the Brian Galibardy period, and a live version is available on a 7 inch single that High Roller Records released along with the vinyl version of the "Save the Khan" album. The only recordings of the other songs are from cassette recorders stuck in the corner of my parents’ front room where we used to rehearse. They definitely aren’t of a release-able quality!

|

Brian Galibardy at The Red Lion. Picture by Rob Grain |

That’s right. These are two songs that I wrote after Graham Legg joined the band, but which we never played with Brian Galibardy. The versions on the High Roller compilations are the demo versions you mention.

“Save the Khan” is such an awesome tune! How did you get that sticky keyboard line?

Thanks! I’m afraid I don’t remember how the keyboard part came about, but part of its feel comes from the fact that it was written on a WASP synthesizer. This was a monophonic instrument (you could only play one note at a time – no chords) with a touch sensitive keyboard (rather than physical keys). It was designed by Rod Argent Keyboards, and I think it was pretty much the first product that made synthesizers available to ordinary punters with less money. Because Mark and I were fans of synthesizer-using bands such as Ultravox! and Kraftwerk, we were super keen to get hold of one of these and my parents bought me one of the first batch to be released in the UK, as an 18th birthday present, which was amazing. I used the WASP on the Save the Khan single.

The lyrics for this song was written by Mark Newbold and that was probably his sole attempt to write lyrics for Triarchy. Did you like the theme he chose for the song? And why didn’t he write more lyrics later?

Mark based the lyrics for "Save the Khan" on a book he’d been reading at the time. In a NWOBHM context, the theme of (something like) solidarity with comrades on the battlefield was great. It’s interesting, though, that I sometimes do a version of the song in my current acoustic live set (more on that later) and I’ve changed the words here and there for that contemporary context, so that there’s rather less emphasis on the macho fighting and rather more on the sadness and futility of the death. I have no idea why Mark didn’t write more lyrics. You’d have to ask him!

What was your plan with the single “Save the Khan”? Did you expect to get a record deal after its release? Or was it just for the sake of capturing your music on vinyl?

As I’ve said, we were all big fans of punk, and from 1976 onwards the punk bands were releasing records on their own labels, selling them at gigs and getting independent distribution deals. In the NWOBHM ranks, both Iron Maiden and Def Leppard had done that too. So we followed suit. We paid for the recording of the "Save the Khan" single ourselves and then we had 1000 copies pressed. Fortunately we very quickly had a distribution deal with Bullet/Neon Records who then paid for a second pressing.

My father was more of a Frank Sinatra fan than he was a metalhead. My mother, however, was an Elvis Presley fan, and, with her more rock’n’roll interests, she also liked bands like Black Sabbath and Steeleye Span, so she was more in tune with our music. Both of my parents were regularly to be seen on the door and selling our records at our gigs at places like the Dartford YMCA.

My father did design the "Metal Messiah" artwork as well as the "Save the Khan" sleeve. And there’s a story there. Bullet/Neon records released the "Metal Messiah" EP, and my father produced artwork for it. But the record was actually released without a picture sleeve. Years later we saw that the original artwork that my father had produced for "Metal Messiah" had changed hands on eBay for nearly $500. We have no idea how the artwork ended up there – presumably some enterprising individual at Bullet/Neon saw an opportunity to make some pocket money. It’s fine, but I’m sorry that my father wasn’t still alive to see it.

“Save the Khan” got some publicity because it was on Geoff Barton’s playlist. And how was “Metal Messiah” received?

"Metal Messiah" definitely didn’t create as big a buzz as "Save the Khan". It’s hard to say exactly why – maybe because although it featured the trademark Triarchy riffs and keyboards, it wasn’t as catchy. I think that, from the tracks on that second release, it was probably our heavy rock version of Robert Johnson’s "Hellhound on my Trail" that attracted most attention. Interestingly, it was never our intention to include "Hellhound..." on that release. However, on the day, we were doing well for time in the studio, so we thought we’d lay down a (nearly) live version of "Hellhound..." as an extra track. That was a good decision. Still, if I look at our Spotify statistics, then, right now anyway, "Metal Messiah" is our most listened to track, so maybe its time has come,

After “Save the Khan” Graham Legg was gone. What happened to him? And how did Brian Galibardy get the job?

This was a complicated moment in Triarchy history. Brian Galibardy had actually been in the band previously, but only briefly and had left because, at the time, he wasn’t into being part of a heavy rock thing. He was more influenced by artists such as Eric Clapton and Little Feat. However, Mark and I always rated his playing and had stayed in touch with him. And later, when Graham was in the band, we had the idea to expand things to a two guitar line-up, combining Brian’s bluesy style with Graham’s rock-y style that also had a bit of new wave in it. So, we convinced Brian to come back and play with us again. I think we had 2 or 3 rehearsals in that format before Graham decided to leave. I think he wanted the band to develop more in an alternative/new-wave direction, but that wasn’t where Mark and I wanted to go. And then Brian stayed on as the lone guitarist, eventually establishing a distinctive live sound that I spoke about earlier. At least we didn’t have to work out what to do about the three-person implications of the name!

I guess when a metalhead sees the title “Metal Messiah”, he expects a song about heavy metal, while your lyrics for this track are about different things. Could you comment on them?

The words move through three scenarios in which control shifts from human to technology, with the metal messiah being a computer of some sort. The scenarios are information held about individuals, war, and some sort of future super-intelligence. They actually prefigure very contemporary worries about AI and the so-called technological singularity. When I listen to the words, I always smile to myself, because, about fifteen years after writing it, I ended up going to university to study philosophy and AI and now, as a professional philosopher, some of my research is still in the area of AI, and although I’m definitely not anti-technology or anti-AI, I have written recently on the dangers present in the ‘shift of control’ issue.

“Sweet Alcohol” has that southern vibe in the middle section. Who brought this to the table?

That was definitely Brian Galibardy who, as I mentioned, was heavily into Southern country boogie bands like Little Feat. His amazing bottleneck slide playing was one of the really distinctive things about the band at that time. I don’t think any of the other NWOBHM bands were using slide in anything like the central way we were, and that was all Brian.

Your version of Robert Johnson’s “Hellhound on my Trail” is incredible! How did you get an idea to turn this bluesy tune to a full speed ahead heavy metal song?

Brian and I both listened to country blues artists like Skip James, Son House and, of course, Robert Johnson. Bands such as Cream and Led Zeppelin had done Johnson songs, or had used parts of them within their own tracks, so it certainly wasn’t unheard of to cover him, but I think our idea was to try to get inside the track in question and capture its edgy feel within a heavy rock format. You won’t find anything like the main riff we use within the Johnson original. That was Brian and me trying to get into the dark underbelly of the track and reimagine it.

Guitarists were the curse of the bands as they came and went constantly. Why did Brian Galibardy leave Triarchy?

As I mentioned earlier, Brian had left the band once before, when he fell out of love with heavy metal and, despite the fact that, second time around, we had enthusiastically incorporated his Clapton-y blues-y playing more centrally into the sound of the band, he just had another moment of doubt that heavy rock was his thing and he left again. In fact, after that, he happily played in country and western bands for a long while.

A guitarist named Justin replaced Brian Galibardy for a while. He even recorded “Rockchild” with the band. What can you say about him as a person and a musician? How come that no one remembers his last name? Did you try to find him later?

This was a bizarre incident. I’m sure Justin turned up as a result of an advert in the music press. He was an interesting guitarist – much wilder in his playing than Brian or Graham, with more energy than subtlety in his playing, something which is very much in evidence on the recording of "Rockchild". I think that wildness was also reflected in the fact that he wasn’t the most disciplined of band-mates – sometimes late to rehearsals, slow to bother to learn the songs accurately etc.. Still, it was fun to crank up the energy levels a bit, and we didn’t throw him out. He just stopped turning up, without a word. I think the "Rockchild" recording session was actually the last time we ever saw him. He wasn’t in the band very long, but I’m really not sure why no one can remember (or even made a note of) his name! We had no practical way of trying to find him later. We hoped that he might come forward on one of the occasions when our material got rereleased, but it never happened.

How did you feel when Mark Newbold gave up drumming? Were you still pretty determined to keep on going? Or did you feel it wasn’t the same without him?

For me personally, that was an incredibly disappointing moment. I mean I respected Mark’s decision – the love had gone out of it for him and he had become more interested in photography – and his leaving had no effect on our long-standing friendship, but it changed things in a very fundamental way. It had been Mark and me through all the different incarnations of the band and, if I say so myself, we had developed into a very fine rhythm section. Although, at that time, I don’t think it ever occurred to me to scrap the Triarchy project, it’s true that, for me, it was never quite the same again.

Could you shed light on the period when you played with Mark Annal (drums), Pete More (guitar) and Eddie Webb? Did you try to write some songs together with these guys?

I just said that Triarchy was never quite the same after Mark Newbold left, and that’s true, but that’s not to say that it wasn’t still good. Mark Annal was a very highly respected local drummer with a powerful double-bass-drum style, and he joined the band, alongside me and the dual lead guitarists Eddie Webb and Pete More, whose styles were like Jimi Hendrix and Angus Young respectively. We did a lot of very good gigs together, including the Horseshoe gigs I mentioned earlier and plenty at The Red Lion. The feel of the band shifted again. One can get an idea of how, if one notes that our repertoire of cover versions that we used to do live changed from things like "Crossroads", "Hey Joe" and "Superstition", songs which were regularly in our set with Brian, to things like "Kick out the Jams", "Search and Destroy" and "Whole Lotta Rosie". I wrote several new songs in that line-up, including one of my all-time favourites, an up-tempo rocker called "Orange and Green" about the Northern Ireland troubles. We planned to record that track as our next single, but I called the end of the band ahead of that happening.

Well, it’s important to start by saying that the project with Mark Dawson and Paul Gunn was never conceived, at the time, as a continuation of Triarchy. Mark had been the lead guitarist in Legend, a splendid NWOBHM band based in Sidcup in South London. Mark also owned and ran his own recording studio – Golddust, which later moved to Bromley and is still active today. Paul had been in Squeeze. We got together purely as a recoding project, exploiting the fact that we had unlimited recording time, because of Mark owning his own studio. That was a big plus but it had its drawbacks, because it really was possible to spend hours and hours fine-tuning a minor percussion overdub that should have taken 15 minutes. We weren’t interested in playing straight heavy rock. We wanted to do things differently. It was relentless experimentation in the studio, with some of the tracks being produced largely as instrumentals before I even thought about a vocal tune or words. That’s why the tracks you mention feel like a departure that doesn’t sound like the old Triarchy (or, indeed Legend) – they really weren’t supposed to. We never played live and, although it was a valuable and productive experience, it didn’t really get beyond first base in terms of any sort of presence. When I was approached in the mid 90s to put together what became Triarchy’s "Beyond your very Ears" collection, Mark Newbold and I decided to include these tracks, because they represented a continuation of my musical work and, well, we liked the songs. It’s worth mentioning that Mark Dawson is now in a really excellent Deep Purple and Led Zeppelin tribute band called Purple Zeppelin.

In my opinion you are very underrated as a lyricist, as your lyrics for “Juliet’s Tomb” or “Before your very Eyes” are brilliant! Would you say that you have a natural talent for lyrics? Did you write lyrics after Triarchy’s demise?

Thanks again! Although I do really like the two sets of lyrics you single out, I don’t consider myself to have a talent for lyrics. It’s not so much that I can’t write them as that it takes me ages to do so, and that in truth I’d much rather be writing the next lot of music, so it’s a massive effort for me to get around to doing it. After Triarchy I joined a band called first The Verse and then Night at the Opera, mainly playing keyboards, and in that band I co-wrote songs with the lead vocalist Doug Moss. I wrote the music and Doug, who’s a fantastic lyricist – much better than me – wrote the words. So that got me off the hook. After that band split up and I went to university, Doug and I drifted apart, but during lockdown we started writing songs together again and these new songs provide the bulk of the material that I now play and record in my current solo stuff, some of which is available on Spotify, iTunes, Bandcamp etc., under the name of Mike Wheeler (see e.g. my 2022 EP called "Stories"). I also play the occasional Triarchy reworking, and I am intending to record and release some of those soon.

Was it an easy decision for you to put the band on ice? What convinced you that it was time to do something else?

The final line-up was the one with Mark Annal, Pete More and Eddie Webb. For me, things just ran out of steam, some time in mid-1982. Mark Annal was unhappy. I’d had to convince him not to leave the band more than once, and, with his final leaving undoubtedly just a matter of time, I decided that I no longer had the energy or the commitment to the Triarchy project to find another new drummer and reboot things again. I don’t think it was an especially difficult decision, but I was sad about it.

What is your favourite memory/story about the Triarchy years?

That would have to be the Red Lion gigs that we did with the Brian Galibardy and Mark Newbold line up, and one of those gigs really sticks in my mind. Mark and I were lounging around early one Friday evening, waiting to go to the pub, and we got a phone call from Terry Lee from the venue to say that the band Spider, who were supposed to be playing that night, had cancelled at the last minute, and he wondered if we could come down and play. A phone call to Brian later and we were on the way. Spider were a hugely enjoyable boogie-style heavy rock band – maybe a bit Status Quo like – and it wasn’t obvious that their crowd were our natural habitat, but we called a couple of Triarchy fans we knew to see if they could swell the ranks of the audience. By the time we went on stage, The Red Lion was packed, not only with Spider fans who had stayed around anyway, and with locals, but with a large number of Triarchy fans who mobilized at a moment’s notice to make the gig, many of them in Triarchy t-shirts that they’d had made and that we hadn’t seen before. We were on top musical form and it turned into a great night.

After Triarchy you became a philosopher and now work in Stirling University. The way from rock music to philosophy is quite long, I must admit. How did that happen?

If I had gone to University at 18, I would have studied English Literature, but I chose not to go then, because of Triarchy. By the time I actually got around to going, I’d started to read some philosophy, but I wasn’t quite sure what I wanted to do. Then, one night, I came in from the pub and, while channel hopping, I can across a debate between a philosopher and an AI researcher on whether we could build a genuinely intelligent machine that had a mind. I was hooked by the issue and sought out a university where I could study philosophy and AI, which happened to be Sussex. I did my PhD at Sussex as well, and then went to Oxford for 4 years as a post-doctoral researcher before moving up to Scotland. I often think that if there had been football on TV that night, I would never have stumbled across that programme, and would never have ended up where I have. Maybe, in some ways, it’s not all that far from music to being an academic – giving talks and lectures is a lot like performing live and there’s a lot of creativity involved in writing papers and books. And, of course, as I explained earlier, the lyrics to Metal Messiah actually prefigured some of my later philosophical concerns.

What is your area of expertise in philosophy?

Philosophy of science (especially cognitive science, psychology, biology, AI) and philosophy of mind. In recent years, I have been mostly concerned with the subtle and complex ways in which human beings intimately couple with technology to transform, enhance, and sometimes impede, our thinking and creativity.

Are your students aware of your music career?

Well, I certainly don’t tend to announce it to all and sundry, but sometimes it comes up in conversation. It’s become more common in recent years for me to talk about it with my students, because my new solo stuff means that I sometimes have to rush off from the university to play a gig, so I have my guitar with me in my office or in a seminar, and then questions will be asked.

Are you still in touch with all the guys who were in Triarchy?

I’m still very close friends with Mark and Martyn Newbold. In recent years I’ve had the occasional beer with Brian Galibardy and Graham Legg. And last year I had a phone conversation with Mark Dawson. I have no idea where any of the other ex-members are. I often expect them to get in touch when Triarchy material gets rereleased, but it hasn’t happened.

There were talks about a reunion in the mid 2000’s. Why didn’t it happen? Would you be up to it these days?

The first couple of times Triarchy reunions were mentioned (roughly, when the "Before your very Ears" and then the "Live to Fight Again" compilations were released), I wasn’t keen, because I was concentrating on my philosophy career. However, when the "Save the Khan" compilation was released, the possibility was raised again and there was mention of a slot at a festival. This time around, and even though I was still busy with my philosophy, I was keen, and Mark Newbold, Graham Legg, Brian Galibardy and I even had some active discussions about it. In the end, however, the idea wouldn’t fly. My line was always that it would have to be the four of us just mentioned who were involved, because to my mind we were the most important band members over the years. But I couldn’t convince Brian to do it, so it didn’t happen. These days I wonder whether I should have been less hardcore about the demand that all four of us be involved, since it would have been fun to play the material again, but that’s the way it goes. I’m proud of what we achieved as a band, and I’m glad and gratified that there’s still a good deal of interest in our music.

No comments:

Post a Comment